Blog: Why we need quality-related funding for research

15 January 2018

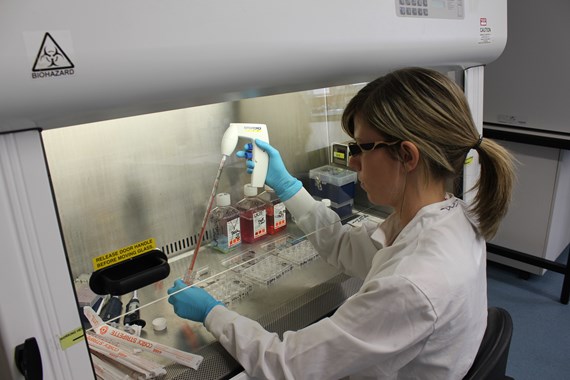

Sarah Chaytor and Graeme Reid, from University College London (UCL) explain why quality-related funding is vital for university research.

Imagine two children, each with a box of Lego. The first child has only one kind of brick, while her friend has lots of different kinds. For a while they play happily at building houses but then the friend decides to build a tree, and then a car and a shop. Soon she has a whole village, all mounted on green base-board. The first child is still building standalone houses, which is all her bricks allow her to do. They are excellent houses but, in the absence of anything to liven up their surroundings or bind them together, they amount to the bleakest of housing estates.

Lego offers an instructive comparison with the UK research base. Project funding from the research councils is enormously valuable, rewarding the best peer-reviewed competitive bids and delivering discrete outputs and impacts. But we need more than that. We also need quality-related funding (QR).

Awarded as block grants to universities, like a big bag of varied Lego bricks, QR funding can be invisible to academics, often being re-branded as “university money” before it reaches the individual departments or research teams whose past performance determines the university’s allocation, via the research excellence framework.

Offering few promises of shiny, headline-grabbing new institutes, this obscurely-named funding stream may seem a dispensable oddity. In fact, it is the bedrock of the UK’s research base. Without QR funding alongside research council, business, European, charity and Innovate UK funding, universities could end up as little more than contractors delivering individual projects. That is a bleak prospect for our currently thriving research base, in which project research is enriched by the broader university context and community in which it takes place.

Children like playing with Lego because the bricks can be used in unpredictable ways, and combined with wheels and hinges to invent lots of structures. The flexibility and agility of QR allows universities to pursue new ideas, support emerging fields of inquiry and offer stable academic careers – with the freedom in at least some cases to pursue research interests without first gaining approval from funding agencies. It allows universities to support early-career researchers beyond employing them as research project assistants. Without it, universities would be under even more pressure to employ all academics either as research contractors on particular research grants or contracts, or as teaching contractors delivering particular courses – making it hard to integrate teaching and research.

Without QR, it would also take longer to grab new opportunities for businesses collaboration or international partnerships. Universities would have less ability to explore new multidisciplinary collaborations unless they were first agreed with research funders, or to participate in projects and institutes whose funders pay less than their full cost.

In short, QR breathes greater intellectual life into universities while rewarding excellence and impact through the REF. That is why the Government’s pledge, in the Industrial Strategy (and underpinned by the enshrining of the ‘balanced funding principle’ in the Higher Education and Research Act) is so welcome. Universities will be able to deliver much more with QR funding to complement the 20 per cent funding increase for project funding announced alongside the industrial strategy – particularly as some of the new schemes require universities to contribute some match-funding.

QR in England currently stands at £1.6 billion per year, and the figure is around £2 billion across the UK. That is a lot of money – but it supports a lot of people and a lot of research, much of which stimulates investment from businesses and research charities. It ensures our university researchers are not simply building Lego houses in isolation but are collectively constructing a thriving and diverse research community from which the entire population benefits.

The Industrial Strategy sets out ambitious plans to take research investment in the UK to internationally competitive levels and harvest the benefits of research to bring productivity gains and greater wellbeing to all parts of the country. Healthy levels of QR funding will be essential to delivering these ambitions.

Sarah Chaytor is Director of Research Strategy & Policy and Graeme Reid is Professor of Science and Research Policy at University College London. An earlier version of this article – with a Christmas twist – was first published in Times Higher Education in December 2017.

-

Jessica Cole

jessica.cole@russellgroup.ac.uk

020 3816 1305

X

X